Back to Characteristics

Title Page

3.6 Teamwork

In the social apostolate the institutional form or set-up varies a great

deal from work to work. This variety is reflected in the different names

used — apostolic community or apostolic team, centre, institute,

project or working group — and the very different types and

levels of activities undertaken: accompaniment, research, grass-roots work,

development, writing, popular movements, advocacy. Working together in

such activities are Jesuits, other religious, professionals, support staff,

volunteers and perhaps others, in varied and complementary roles.

What basically unites all these people is the daily work. This depends

on some form of organisation, which can be simple or sophisticated depending

on the history and circumstances of the project. Organisation — whether

of a tiny project or of a multi-purpose centre — includes the distribution

of tasks, the efficient use of human and material resources. It may also

include planning, sharing social analysis, evaluation, coordinated research

and action. These aspects do much to develop the staff and form a team.

Working as a Jesuit apostolic team includes good organisation but also

goes deeper. It becomes really possible if each member occasionally shares

with the others at the level of beliefs, hopes and values. In the sharing,

each person's vocation becomes manifest in its integrity. As competence,

dedication, energy, affection and good humour come together, the team gains

in substance, spirit and identity.

Teamwork, not only an internal matter, is a significant form of witness.

What we do together and how we do it together give more credible testimony

than words alone to what we believe in, hope for and work for. Our teamwork

is not just efficient and productive but, with our faith and hope shining

through, effective in service and social change.

Þ

On-going Tensions (4.2)

|

| Relationships of openness and trust

Every culture has preferred ways of organising work. While each group

can probably learn, inter-culturally, from approaches used elsewhere in

the social apostolate, there is no question of imposing a single way of

working together. The purpose here is to help discover what might be done

to strengthen teamwork, and the present reflection must be adapted with

sensitivity to the local situation.

To encourage and develop teamwork, the following are usually helpful:

· formation of staff

· clarity of roles and goals

· giving/taking appropriate responsibility

· conflict resolution in a culturally

appropriate manner

· leadership which listens to the

members and cares for them

· proper structures of accountability

for both staff and leaders |

We participants were drawn from all walks of life within the Society:

old and young; various nationalities, experiences, professions, status,

language. But amazingly we were able to communicate and listen to one another

without any form of discrimination or complex. It reminded me of stories

of the first Pentecost! This was the Society of Jesus I wanted to join,

live and die in when I freely became a member several years ago. (Joakim

Mtima Chisemphere at Naples)

|

Pg - 48 - Promoting the work — Teamwork

The fundamental bases on which as staff we want to work with one another

are relationships of openness and trust, with a high degree of consultation,

dialogue and involvement in decision-making.

Listening is always at the origin of working together! Listening

may be a human gift which some have more than others, but everyone can

probably learn it. It begins with taking time rather than being too busy,

and giving full attention to the one speaking. To listen is to let go of

one's own task, role or expertise, to set fears and frustrations aside,

and to look beyond the first meaning (often the cause of misunderstanding)

for the experience and real intent behind the other's words. Be more eager

to put a good interpretation on another's statement than to condemn it,

advises St. Ignatius at the beginning of the Spiritual Exercises,

and presuppose that the other person is doing the same.

Lack of listening may not be the root of all staff problems, but without

good listening teamwork is surely impossible.

|

We make up work teams with other persons: inter-disciplinary

teams which seriously face the challenges of our time, requiring creativity

and a critical attitude with sensitivity to the life of the people whom

they accompany and from whom they learn; teams open to regional, national

and world realities, motivated to establish relationships with other teams,

accomplishing professional work motivated by the following of Jesus. (Latin

America)

|

Each one needs to try to listen, but as a group

it is also important to clear some space and set aside time to speak together,

sort out our disagreements, clarify our misunderstandings, and develop

a common language for communicating with ease and security. These are skills

which an outside facilitator may help us to learn.

Good communication allows us to put important things "on the table"

for discussion, and this mutuality and transparency are the basis for teamwork

and participation in decision-making. To find the right points and an appropriate

way to discuss them is probably the role of leadership. Everything is not

equally or identically discussable by everyone. Hopefully every Jesuit

social apostolate, from a simple group or collective to an articulated

institution, can become a team or include teamwork in this full sense. |

Styles of Working

Considering a Jesuit social project, here are some "types" which, when

put together, show the variety of persons involved:

| status

Jesuit

other religious

person with family

single |

work

administration

programme

support

ad omnia |

category

professional

support staff

intern/trainee

volunteer |

origin

local

national

from another country

of a different culture |

Such combinations of types usually produce a rich complementarity, but

they can also sometimes lead to friction. For example, professional staff

vs support staff vs volunteers; those who earn

Teamwork - pg - 49 -

more vs those who earn less vs those who do not earn; those with families

vs single people vs Jesuits.

Besides persons, a style also colours the whole work. Within

a project, relationships can be quite informal, the tasks distributed flexibly,

and leadership exercised in an inspirational or charismatic way.

Everyone appreciates an esprit de corps which motivates and supports

the members and which communicates the intrinsic worth of the project to

others who, in turn, are attracted as volunteers. However, a charismatic

or informal style may prove inefficient in the use of resources, reluctant

to adapt to new challenges, awkward in integrating new staff. The leadership,

if dominated by personality, may not allow the members their proper autonomy

and responsibility within the organisation.

The social apostolate also uses an institutional or professional

style which puts the premium on competence. Instead of being informal,

roles and functions are differentiated. Here we find features like clear

distribution of tasks, lines of authority, areas of responsibility, planning

and management, contracts between employer and employee, fair scales of

pay and benefits. Such conditions help make sustained teamwork possible.

The work is seen to be of good quality, and this generates confidence and

support from the public and the Church. An institutional style can also

suffer, especially if the centre or institution grows too large, inaccessible

to the poor and bureaucratic in dealing with people. Attachment to jobs

or professionalism in the pejorative sense can replace dedication to the

work of service. Once rigidity sets in, the institutional style becomes

difficult to renew.

Each project is a particular mix or permutation of informal, inspirational,

institutional and professional elements. For it to work well, the complementary

roles and contributions of support staff, professionals and leadership

need to be appreciated. The combinations, in reality, are not always easy

— if a project becomes so professionalised that the volunteers get squeezed

out; if a volunteer working out of free personal commitment misjudges an

employee doing a paid job; if an inadequate salary scale makes it impossible

for people to continue when married; if leadership is heavy-handed; if

administration becomes bureaucratic.

| Some shortcomings are inevitable, but a Jesuit

social project can also sin through authoritarianism or clericalism, through

discrimination against minorities and in particular against women, through

systematic under-appreciation of the worth and dignity of certain persons

on staff. Our mission to promote the justice of God's kingdom behooves

us to face such sins and make every effort to reform, even at great expense

or pain.

Teamwork does not mean that everyone gets involved in everything, but

that the various contributions come together. For this it is important

that a team really have coordination, not only in action but also

at the level of research and reflection, where the great challenge of developing

effective interdisciplinary teamwork awaits us. |

Partnership of the laity in social apostolate is a significant

phenomenon for us today. Lay men and women can often be true witnesses

of the mission. Hence, it is expected that they are enabled to identify

themselves with the mission, and participate in greater measure in the

decision processes. The question is: To what extent have they experienced

this identification and participation?

(Naples Congress)

|

Pg - 50 - Promoting the work — Teamwork 3.6

Finally, rather than types or styles, it is people who make up a team,

and we know it works when we perceive spontaneity, generosity, clarity,

gratuity, security, dedication, effectiveness, simplicity. Are these present

in our work?

Jesuit-lay collaboration

Each role or category — employer, employee, professional, support staff,

full-timer, intern, volunteer — can be filled by a Jesuit, other religious,

single person or someone with a family. Fundamentally, each group needs

to understand and appreciate the strengths and constraints typical of the

others.

Lay people have much to offer, including occupations or professions

which are essential for bringing greater justice to society and culture.

At the same time, lay people have needs in terms of income, commitments

to family, professional development, job security, social life.

Jesuits and members of other religious congregations offer their personal

and professional competence, often shaped by their religious formation;

they bring their special links with the Church; they can share their spiritual

heritage and a style of leadership which makes possible the work of others.

They also have needs and constraints typical of community life, the availability

which obedience requires, commitments to the Society or Congregation.

Mutual understanding and respect, therefore, are indispensable: a real

appreciation of the dignity, equality and difference in the lay and Jesuit

vocations, and a readiness to recognise the gifts, needs and sensitivities

typical of each group.

In the social apostolate there is a great variety of working relationships

between Jesuits and non-Jesuits. Focusing mainly on projects or institutions

which the Society sponsors and directs, the Jesuits owe it to our co-workers

to give a clear and transparent account of our aim and purpose. A work

for which the Society takes ultimate responsibility "must be guided by

a clear mission statement which outlines the purposes of the work and forms

the basis for collaboration in it. This mission statement should be presented

and clearly explained to those with whom we cooperate" (GC34, d.13, n.12).

A Jesuit in a non-Jesuit work like a trade union, popular movement or UN

research centre has the opportunity to share with others what we are trying

to do in the social apostolate (n.14).

Moreover, we Jesuits may give testimony, in word and deed, in freedom

and vulnerability, of our life as followers of Christ in the Society of

Jesus. Some will resonate with this testimony. Christian colleagues of

an Ignatian formation and spirituality join in implementing our mission.

Þ

Origin (1.)  —

Vision (5.)

—

Vision (5.)

Religious of other congregations and other Christians are similarly

invited to express the faith as followers of Jesus Christ and members of

his Church and the spirituality which motivates their social justice work.

Those of other faiths and spiritualities are welcome to do the same, and

secular-minded colleagues to share their important human and cultural values.

There are fears and hesitations which might block this deeper communication.

Earlier sins of intolerance or proselytism; a false respect for the sensitivities

of our colleagues be they Christians, of another faith or of none; the

implied or express rejection by others of Christian

Some co-workers have roots in social action, in the parliament

of the streets. Some come from a faith (although not necessarily Church)

premise. Others come from a secularist-humanist concern for justice and

now search for transcendent foundations of their social action. For some,

it is mainly a job, and so the need for clear terms, conditions, job description,

staff appraisal.

(East Asia)

|

faith, the Church or Ignatian spirituality —

any of these may discourage Jesuits from trying to communicate our deepest

inspiration. It is up to us to find an appropriate, transparent manner

of doing so. At the same time, since it is the Jesuit social apostolate

we are working in, the tradition and full reality of the Society of Jesus

constitute an important "given." Without imposing, they establish a realm

of meaning and discourse with both content and limits, so that religious,

moral and spiritual issues are not simply up for open-ended debate.

Þ

Religious Reading (3.5)

|

Although there is a risk of sharp disagreements and even conflict, and

although there are situations where silence is the appropriate respectful

attitude, a taboo should not be allowed to cover all such issues. We have

much to learn from the variety of one another's humanism, social vision,

faith and spirituality.

Formation

All staff should have the chance to avail themselves of opportunities

to increase their competence, through informal training as well as formal

education.

The Jesuits, as sponsors of the social project, should inform the staff

about the Province and the Society, share relevant materials such as decrees

of recent General Congregations or certain letters of Father General, and

offer those who are interested an on-going formation in Ignatian spirituality.

In addition, just as we Jesuits want to share our vision and spirituality,

we also have much to learn from others and are happy to.

The Ignatian charism would have us find God in all things, and the Jesuit

charism would embody this mysticism in a concrete work. It is in this spirit

that each social project or centre would like to have bonds of friendship

and kindred spirits and a real working community.

To invoke a dynamic of openness in this way, which is also a

dynamic of solidarity and hospitality and compassion, is to thank the many

Jesuits and many non-Jesuits who at the inevitable risk of connivance have

helped the Church of the Lord learn to become fraternal again and welcoming

to the life of the poor and to work with all people in building a more

human world.

(Father General at Naples)

|

Pg - 52 - Teamwork 3.6

Questions

1. Which aspects of an institutional, professional model and which of

an inspirational, informal one are found in our centre or project? What

would help us work more as a team?

2. How are characteristics, vision and mission to be discussed between

Jesuits and colleagues? Are there opportunities for sharing and formation?

3. How are authority, decision making and accountability exercised and

shared?

4. What is the identity of the project: Jesuit, Ignatian, Christian,

independent, non-confessional, secular? How does this identity shape relationships

between Jesuits and non-Jesuits on the staff?

3.7 Cooperation and Networking

Cooperation and networking of all types probably represent an authentic

sign

of the times in the sense meant by Vatican II: something new emerging

simultaneously in different places, something both challenging and promising

in the light of the Gospel.

The poverty, suffering, exclusion, injustice and violence we deal with

are enough to overwhelm even the most dedicated or sophisticated project

of the social apostolate. Therefore our projects and ministries must work

with others. We pool our creativity, intelligence and strengths with those

of others to face problems of great scale and complexity; and our cooperation

itself is a significant witness to the solidarity and justice that we believe

in, hope for, work for.

A great deal of cooperation in the promotion of justice is already underway,

and some efforts have been very effective. We want to learn from these

and reinforce them. At the same time, networking as an approach to social

injustice is relatively new and sometimes quite difficult in practice,

and we want to be realistic in facing the problems and resistance.

This chapter considers cooperation within the social sector in each

Province and Assistancy; cooperation with Jesuits and colleagues in other

sectors; and cooperation with other social centres, projects, organisations

and movements at every level. In each case, we will try to discover what

might be done to enhance both our cooperation within the social apostolate

and our contribution to networking with others, to promote the justice

of the Kingdom.

Sectoral cooperation

Þ

The Jesuit body (3.10)

Within the social apostolate, we look back over several decades of much

creativity, deep fidelity, fraternity and cooperation. We also notice the

vigorous spirit with which strong positions were taken, which sometimes

made it difficult to step back and find the distance to listen to one another.

We realize that a passionate and prophetic commitment to a social cause

should not exclude listening to others. When it does, those who do not

listen eventually become isolated, and the net result is to weaken the

social apostolate, that is, our corporate response to poverty, suffering

and injustice.

Lack of listening and non-cooperation are serious defects and not without

their irony. Those who know us are often struck by the strong ties among

Jesuits generated by our common spirituality and tradition and nurtured

through a long course of formation. Logically, these fraternal links as

Jesuit companions should translate into an extensive and effective web

of contacts among all sorts of Jesuit efforts and projects. Fine long-running

examples of such cooperation already exist.

Among the many factors which contribute to the life of the social sector

in each Province, we may distinguish two kinds of cooperation, one based

on the issues and the other accenting the approach or disciplines

we

use.

The issues themselves can bring together social apostolate projects

of similar kinds within a Province or in different Provinces. For example,

those who are dealing with unemployment, homelessness, drugs, urban youth,

human rights, have much experience worth sharing — at least for the sake

of learning and mutual support, but perhaps also to help one another, coordinate

efforts, join forces. This can only enhance the justice which each effort

is striving for in its own way, while at the same time strengthening the

social sector we belong to.

Pg - 54 - Promoting the work — Cooperation and Networking

Some Jesuit projects are networking with their counterparts in other

Provinces, for example, Jesuit Volunteer programmes, Jesuit social scientists

in Europe, prison chaplains in North America, ministry among indigenous

peoples or the urban poor in Latin America.

The other characteristic form of working together is between different

disciplines and levels. The cheerful image evoked at the Naples Congress

of "head" linked with "feet" is in fact a very high and very promising

ideal. It means connecting direct and organisational involvement among

the poor, reading of and research into social reality, and action on culture

and structures.

Þ On-going

Tensions (4.2)

Even within an individual Jesuit or lay colleague, "head" and "feet"

can exist as a healthy tension: a Jesuit inserted among the poor who works

as a competent social scientist, or a social researcher who is directly

involved with the poor.

| Such personal integration contributes to the

still greater challenge of developing working relationships at the Province,

Assistancy and Society levels. Thus, individuals involved in Jesuit projects

and centres at a geographical and social distance from one another exchange

experience and insight, not as fmished results but as complementary inputs

into an on-going common effort. Social research centres and centres for

faith and new points of contact with other types and levels of social action.

"Head" and "feet" learning to work together, besides giving fresh impetus

to the social apostolate, may allow us to take up a fundamental challenge

in our field. Socio-cultural reality is so complex that no social science

by itself, nor the social sciences put together, nor even a broad practical

approach like "Human Development" put forward by the United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP) offers a promising method for comprehending it. Action

and reflection in the social area need to be connected on a new basis.

The basis could be habitual collaboration between some who reflect critically

on social issues and formulate theories, and others who work actively in

the field. |

A central strategy of much Jesuit social ministry involves strengthening

local communities, encouraging participation in community building, and

culture, whether free-standing or based at universities, find developing

local connections to wider social resources and networks. Usually such

social ministry is highly collaborative, with Jesuits working side by side

with lay men and women, members of other religious com munities and other

local organizations.

(United States)

|

Each may profit from the experience and insight of the other: the theoreticians

in closer touch with lived problems of poverty and injustice, the practitioners

absorbing perspectives of analysis which give quality to the direct, developmental

or organisational assistance which they offer, and both as they make their

impact in the public sphere.

Cooperation involves more than merely juxtaposing the current methodologies

of analysis or critical reading with fieldwork as currently practised.

Rather than just hope that something interesting might emerge, we can learn

to combine the typically isolated enterprises of "head" and "feet" into

an integrated approach to social reality bringing direct experience, social

sciences, philosophy and theology together. The task is to forge a valid

inter-disciplinary approach for the sake of greater justice, and the Jesuit

social apostolate is perhaps uniquely placed to take up the challenge.

Cooperation and Networking - pg - 55 -

Instead of lamenting the individualism and fragmentation typical of

our day, we can learn to combine "head" and "feet" within a shared mission

on a worldwide basis, maybe a unique chance to find new intellectual and

practical methods for the promotion of justice.

Cooperation with other Jesuits and colleagues

The social apostolate has much to learn and receive from other apostolic

sectors and also much to offer to the rest of the Province: to other ministries,

formation, community life, vocation promotion and volunteer programmes.

The Social Apostolate Initiative is meant to facilitate better communication,

interchange and mutual support between the social sector and the rest of

the Province. Þ The

Social Apostolate Initiative (Appendix B.)

But given the sometimes difficult history we have travelled (some of

whose consequences are still with us), what is the best way to foster such

cooperation?

One option is for the social sector to wait until others approach us

and ask for information or suggestions. For example, a Jesuit finds himself

distant from the poor and asks for ideas about living or working in a more

inserted manner; or a Jesuit community wishes to draw nearer to the poor

and asks for suggestions on how to exercise effective solidarity.

Another option is for members of this apostolate, avoiding blanket criticisms

or general advice, to propose specific occasions for cooperation. Thus,

Jesuits working in the social sector could approach a Jesuit school of

business administration to develop appropriate accounting techniques; develop

techniques of reflection on social experiences for candidates, novices,

high school or university students; ask a media Jesuit to make video available

as

a tool for work on social issues in a poor neighbourhood; approach retired

Jesuits who may be willing to tutor kids in difficulty or visit with MDS

sufferers or homeless people; or ask Jesuits in the infirmary to pray for

suffering or despairing persons.

Cooperation is so important that it is worth preparing carefully. The

social sector, for its part, is taking time during the current Initiative

to clarify its purpose and discourse, a positive step towards working effectively

with other sectors which have a long and steady apostolic history.

The open possibilities for communication with fax and electronic mail

allow Jesuits to work together internationally in the area of social justice.

Examples include:

· the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS)

in the campaign against landmines;

· Jesuits for Debt Relief and Development

(JDRAD) on the cancellation of the external debt crushing very poor countries;

· International Population Concerns

(IPC) on demography and poverty;

· the consult on globalisation based

at the Woodstock Center in the United States;

· the electronic-mail list, called

"sj social," for discussion of justice issues and the exchange of information.

Þ Resources (Appendix D.)

There are many issues such as environmental protection and the reform

of international institutions on which we could work together internationally.

GC34 recommends international work with communities of solidarity in supporting

the full range of human rights (d.3, n.6).

Pg - 56 - Promoting the work

Cooperation with others

| Those with whom we cooperate may be individuals,

groups and organisations, public entities (municipal, state and national

levels), the Church, intergovernmental bodies. The types of cooperation

include exchange of information or joint work on specific issues, involvement

in coalitions and participation in networks.

Cooperation takes place on all levels from local through regional to

international, with at times complex inter-relationships running through

different levels of a single problem. GC34 strongly encouraged regional

and worldwide cooperation: |

In many respects, the future of international cooperation remains

largely uncharted. With creative imagination, openness and humility, we

must be ready to cooperate with all those working for the integral development

and liberation of people. (GC34)

|

Such networks of persons and institutions should be capable of

addressing global concerns through support, sharing of information, planning

and evaluation, or through implementation of projects that cannot easily

be carried Out within Province structures. The potential exists for networks

of specialists who differ in expertise and perspectives but who share a

common concern, as well as for networks of university departments, research

centres, scholarly journals and regional advocacy groups. The potential

also exists for cooperation in and through international agencies, non-governmental

organisations, and other emerging associations of men and women of good

will (d.21, n.14).

The work, the issue, the cause is what brings us together. What do we of

the Jesuit social apostolate have to offer? Based on our experience as

a worldwide body, rooted deeply in a particular place but with international

contacts and perspectives, we can contribute much to the networks of organisations

concerned with social and global issues: witness, vision, method, connections,

ethics, know-how.

While the work or issue brings us together, experience shows that it

may be easier to unite against than it is to agree on what alternative

or change to work for. Moreover, are there values which prove incompatible,

or is the issue itself enough to render all differences "indifferent"?

It may be necessary, though painful, to take a stand on issues of life,

arms or non-violence, ethical issues like plagiarism or defamation, or

social issues like ethnic chauvinism or religious bigotry -even at the

risk of weakening or leaving a coalition.

The impulse to cooperate comes from the experience of the complexity

of social issues in a "globalising" world and the relative powerlessness

of each individual effort. Successive technologies (telex, fax, e-mail)

make networking ever more possible and inexpensive. A proposal to set up

a network usually meets with initial enthusiasm, but unless the network's

purpose and rules are clear, however, those enlisted are unlikely to make

use of it. Effective networking, like any other social project, requires

good planning, leadership, discipline and resources. A network can serve

quite different, related or overlapping purposes: urgent action, exchange

of "hard" information, exchange of "soft" news, cooperation on a common

project, advocacy or lobbying, monitoring public or global institutions

(the national government, the United Nations) or participating in a special

event like the Rio, Copenhagen or Beijing conference.

Cooperation and Networking - pg -57 -

| In the process of cooperation at whatever level,

working with others to have an effect on society, differences that used

to put distance and even opposition between groups, prove interesting and

even complementary resources. If cooperation is a real priority, then our

social project or centre invests time and human and material resources

in cooperation and develops a work agenda in common with other groups.

A real commitment to cooperation, which often means sacrificing one's

own preferences or immediate interests, shows that we do not consider ourselves

or our project the sole or entire solution. On the contrary, we happily

acknowledge complexity, diversity and pluralism, and we affirm cooperation

itself as a positive value — for its efficiency and for its cultural

and evangelical effectiveness. It is an important sign of the times and

an expressive witness to the kind of world we hope and work for. |

We try to live the principles of a future society to which we contribute

with the work we do, such as: respect for personal freedom, solidarity,

pluralism, commitment to justice, fraternity and democracy in decision-making.

(Latin America)

|

Questions

1. Are there examples of cooperation in this Province between

individuals or works in the social sector and individuals or works in other

apostolic sectors. How might such cooperation develop?

2. What are some successful examples of local cooperation and broader

networking that you know of? Are there some unhappy ones? What factors

have significantly contributed to or worked against the success of these

efforts?

3. What values do cooperation and networking both realize and project?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of technologies like fax, e-mail,

the Internet, the World Wide Web? In what ways has technology facilitated

networking and promoted justice?

3.8 Planning and Evaluation

- pg - 59 -

In every Jesuit social project, a constant exchange of information,

impressions and new ideas is going on, and so planning and evaluation are

always taking place: informally and implicitly in the midst of the work;

in routine meetings and tasks which make up our working together; and in

occasional, more or less formal procedures.

Evaluation examines what we set out to do, how we implemented our programme

of research and action, what has been achieved. Planning, having gathered

the relevant factors, proposes new approaches to achieving what we earlier

set out to do or, more profoundly, formulates new objectives.

There is much overlap: evaluation tends to look back for the sake of

the work in future, while planning looks forward on the basis of assessing

the relevant factors both in the field and within the project. All planning

involves some evaluation, and all evaluation has implications for planning.

A great deal of know-how concerning evaluation and planning is available

from manuals, experienced facilitators and staff members of other social

justice and Church groups. The present chapter — not a full treatment in

itself — helps to identify the steps or resources that might be needed.

Discernment, which marks all our evaluation and planning but cannot be

reduced to these, characterizes the entire social apostolate and is treated

separately in chapter 4.1.

Beginning with the evaluation and planning already going on, we review

the features of the process, consider the components of our social apostolate

being evaluated and planned, and conclude with larger themes our planning

and evaluation raise.

Informal, regular and formal occasions

In the daily flow of work, staff members constantly meet and ask one

another: "How are things going? What's new? Has something gone awry? What

are you doing next?" This informal interchange, with its typical asking,

recounting, probing and verifying, willy nilly includes elements of planning

and evaluation.

Things may generally be going well — everyone on staff busy, much output

and outreach, many needs being met, donors sending support. However, these

facts (or impressions!) do not render superfluous a deliberate effort to

examine our activities and programmes.

Many Jesuit working groups regularly set aside some time (a morning,

a day, a weekend) to report on activities, bring everyone up to date, take

stock and make suggestions. More explicit evaluation and planning are usually

involved when hiring staff, redistributing tasks, finishing up a project,

taking up new work, applying for funds, writing a report, budgeting for

the coming year. Informal evaluation may lead to an improvement in how

things are done.

Those unfamiliar with good process may resist planning and evaluation

as pretexts for intrusion and inspection or simply as a waste of time.

There is also the fear of changes that might result or the opposite fear

that a congratulatory rather than self-critical exercise will paper over

what is really amiss. Despite these fears, evaluating and planning, competently

undertaken and followed through, bring many essential benefits.

Pg - 60 - Promoting the work — Planning and Evaluation

Prom time to time, a Jesuit social centre or project may deliberately

undertake a formal process of evaluation and planning. There are a number

of valid reasons that motivate a social work to take stock formally and

set goals and objectives for the future:

· Significant changes occur among

the people served or the issues worked on.

· External demands seem to overwhelm

all plans and determine priorities, and staff members feel overloaded.

· The people we work with or the

groups we collaborate with suggest new directions.

· The work seems to lack focus or

the results leave us dissatisfied.

· The staff faces an important transition

such as finding a successor to the founding director.

· A funding agency requires a full

report.

· The Province apostolic plan requests

an account of the ministry.

In the following, it helps to choose either evaluation or planning as

the focus for reflection and to keep a specific social centre, work or

community in mind. The concerns also apply, in different ways, to the whole

social sector in a Province and may usefully be taken up by the social

commission or by coordinators meeting at the Assistancy level. If a point

seems too obvious to be worth mentioning, please remember that in another

project or Province, or in this project or Province at another time, the

same point may be very relevant.

Ingredients

Planning and evaluation — whether a one-off meeting, a regular series,

or a formal process -themselves need to be reviewed, to see if they are

well-designed and running well. The purpose here is to look over some basic

elements that are usually involved, to see which weak or missing ones are

subject to improvement.

Planning and evaluation are shaped by those who commission the exercise,

those who design and conduct it, and those who participate in it. Evaluation

may be commissioned by the project or centre itself (either the leadership

or the whole group), by funding agencies, by the sponsoring Province.

An external evaluation is designed and conducted by outsiders,

with more or less involvement of the staff. When a problem runs very deep,

for example, the leadership or the whole staff is in crisis, then evaluation

generally needs to be external if it is to be credible and effective.

An internal evaluation is designed and conducted by the centre

or project itself and is, in this sense, a self-evaluation, while

planning is by nature internal. Both can benefit from the expert and dis-interested

help offered by facilitators (design, group dynamics) or technical consultants

(financial auditing, statistical sampling).

Experience shows that whether evaluation is internal or external, participation

is most important. The active participants may be the leadership or administration,

or the professional staff, or the whole staff. An evaluation involving

as many of those engaged in the work as possible gives better findings

and makes the implementation of recommendations or planning much easier.

Beneficiaries of our services, groups we collaborate with, NGOs or public

agencies, funders and Church representatives may also be invited to participate.

Planning and Evaluation - pg - 61 -

A second concern is the design of the evaluation or planning. It is

essential to define the purpose or objectives as precisely as possible.

What needs exactly are to be met? What are the most important questions

to be answered? If the questions are about success or failure, how are

these terms defined, and who (external evaluators, leadership, professionals,

staff) establish the criteria? How are the constraints that establish the

limits of the project's viability to be found and faced? Does our socio-cultural

analysis inform our planning and evaluation?

| A third set of issues may be found in the method

or style. For example, a different approach is used to prepare a year's

work than to review the overall mission. It is important to establish an

appropriate calendar: a hasty process risks superficiality, a prolonged

one may drag down all the other activities. Another aspect is the level

or scope: can the problems that are identified be solved on their own or

do they point to a deeper malaise?

A final set of questions about the outcome needs to be faced at the

beginning. What are the hoped for results? What is the range of possible

changes? Being ready to draw the fruit from evaluation or foreseeing how

planning will be implemented help to keep the process honest and modest,

feasible and focused, and are convincing pledges of its seriousness. |

Let us develop methods and techniques of planning which arise from

a reading of social reality in which we are inserted, a reading from the

perspective of the poor and constantly up-dated by the frequent practice

of social analysis.

(Latin America)

|

Components of our work

We now look at what is being evaluated and planned: Which components

— whether of a whole centre or work, a single department, or a particular

programme — are going well? Is something needed to maintain them? Are they

worth strengthening? Is a component overlooked or neglected and, if so,

how can it be brought in?

As all our work is finally for and with others, the first questions

may well have to do with efficacy and impact: how the work or centre meets

the real needs of people in society and the Church. We need to look at

the results — admittedly hard to appreciate, much less quantify -and ask

whether they are what earlier planning would lead us to expect. Are they

in harmony with our mission? Are they sufficient? Are they unexpected?

Our research and writing may "produce" useful things, but do these get

out and reach people? We may do good workshops and communicate effectively,

but does sufficient research support the activities?

Intrinsic to the work of our project or centre is its "reading" of society.

Despite our good reputation in this area, as a staff we might rarely share

our analysis with one another, much less verify if it has become routine

or is really perceptive of new problems emerging and responsive to change.

Is our analysis precise, and adequate to the complexities?

Our social, cultural, evangelical effectiveness depends very much on

how staff members work together. Appropriate levels of openness and participation

are important. Evaluation and planning can look at what really gets put

in common on the table, and whether we make use of opportunities for constructive

criticism or tend to avoid them. Cliques or divisions, individualism, careerism

and neglect of coordination are obstacles to teamwork. Evaluation and planning

are opportunities for a team to coalesce and take active responsibility

for its work.

Pg - 62 - Promoting the work — Planning and Evaluation

|

It seems that our approach to social analysis up to now has

often been too narrow, focusing on the economic dimension to the neglect

of the cultural, spiritual and ecological aspects. Such a fundamental question

is very much the "business" of an evaluation. (Africa)

|

Since so much depends on collaboration, we might

evaluate our links with sister groups and consult some of them in our planning.

Otherwise we run the typical danger of appearing too busy or independent

to cooperate with others.

Without reducing everything to professionalism, we want to employ professional

and intellectual skills in all our social ministry. Is the work well set

up, efficiently run, productive? Is creativity encouraged? Does the outcome

of the project warrant the human, financial and material resources employed? |

Given the undertaking, are these insufficient? Given the resources,

are the expectations realistic or not? Is the work cost-effective and sustainable

and can it be replicated? To ask if we should cut back, change focus or

wind down may seem threatening since a work, once institutionalised, operates

on the presumption that it will carry on and usually grow.

| The way in which decisions are reached is another

area to be examined. Is there incisive evaluation and proactive planning?

This area also involves looking at the way in which leadership contributes

to the life of the team and the quality of the ministry. Does it find a

balance between authoritarian excess and the anarchy of everyone deciding

everything?

The needs are usually enormous and endless, and the work done obviously

relevant. But is it well thought out? Is this the best way of running it?

For example, does the technology we use show simplicity? Does it enhance

both productivity and the service of justice? Or does it distance us from

sister groups and the people we serve? The material, financial, infrastructural

means used also need to be examined to see whether they are effective,

in harmony with local culture, and of some witness value. |

Very significant Social Apostolate works are frequently developed

by talented and hard working Jesuits who do not involve themselves in a

team approach. Their efforts are highly personalised in planning administration,

fund raising, and evaluation. Often they bear only a tenuous relationship

to the local province or region not being a corporate apostolate. Younger

Jesuits are not encouraged to be involved in the work nor adequately prepared

to take over responsibilities for it. As a consequence the work may simply

die out when the Jesuit dies or leaves the area. (Africa)

|

Finally, how does the particular centre or project participate in the

social sector of the Province, and how does the Province exercise care

for the work? Are young members of the Province familiar with and supportive

of the project, and do some of them foresee being involved in future? Or

is the work, even though located within the Province territory, not a "corporate

apostolate" but outside the social sector and the Province mission? If

so, what might be done to bridge these gaps?

Planning and evaluation, in the spirit of Characteristics, involve

looking for the questions which cannot not be asked. Sometimes,

for both objective and emotional reasons, these questions are difficult

to find and raise. It is also difficult for a group to be self-critical

and face change. Despite obstacles and resistance, though, we should find

which steps (few or many, big or small)

Planning and Evaluation - pg - 63 -

| are needed in this particular work or

social sector at this time: the grace to see, and the strength to

do.

Themes for reflection

Planning and evaluating sometimes uncover broad, deep themes worth thinking

over in our work and also in our community life.

The Jesuit social apostolate does not invent its own mission but receives

it from the Society of Jesus: to bring the faith and justice of the Gospel

to society and culture. Each work, project, centre or community implements

mission and in turn contributes to the whole sector and the overall Province

mission. |

Jesuit institutions can use the following means to help in implementing

our mission: institutional evaluation of the role they play in society;

examination of whether the institution's own internal structures and policies

reflect our mission; collaboration and exchange with similar institutions

in diverse social and cultural contexts; continuing formation of personnel

regarding mission. (GC 34)

|

Do our work and way of life fulfil the mission integrally or — as is

sometimes the case — do they respond to motivations which are intellectual,

ideological or psychological in nature?

To work well requires organizational efficiency and professional competence,

and in vital tension with these are Gospel values of charity, forgiveness,

gratuity and reconciliation. At the same time, the Gospel is no substitute

for competence and organization, no excuse for complacency or sloppiness.

Effectiveness in service of the poor is not identical with, but mysteriously

greater than, "bottom line" efficiency according to the dominant system.

Preaching in poverty is accomplished, paradoxically, by struggling

in poverty, with all competence and professionalism, with all the effective

planning and indispensable strategies, because the poor deserve to have

the best, the magis of our effort. For we make use of these impressive

means, not to our own advantage, but always with generosity, gratuity and

non-violence which mark the commitment to the service of others, all the

way without turning back and without recompense (Father General at Naples).

The immediate objectives, the means of achieving them, may become all-absorbing;

the project or institute may have obeyed the "natural" logic of expansion

rather than grow (or not!) according to evaluation and planning which take

the mission as foundational.

Seeking to promote the justice of the Kingdom, it is not easy to evaluate

the fruits. Some results are perceivable and objectively appreciable, but

many others — connected with people's conversion and social transformation

— are invisible yet very real, with direct or indirect effects on individuals

and communities, culture and structures.

Differentiating between success and failure — real, apparent, short-term

and long-term — is a matter of the criteria that are obeyed in practice.

Does what we do and live translate our mission into reality and convey

our vision to others, or do these ideals actually get reduced to the tasks

that take up all our time? Our day-to-day practice communicates unerringly,

far more accurately than words, the values we really embrace.

Pg - 64 - Promoting the work — Planning and Evaluation

Mistakes made in the socio-cultural field may have wide repercussions

and lasting effects on others and ourselves. Some are practically inevitable,

others avoidable. Let us learn from failures, celebrate successes, learn

and grow through both.

Evaluation and planning mean paying attention to the culture which our

ministry is promoting: the model of society which is being encouraged,

the political impact, the ethical meaning, the evangelical significance.

They present a continuous opportunity to make what we do and live, in a

social centre or project and an entire sector, ever more truly characteristic

of the Jesuit social apostolate.

Questions

1. What planning and evaluating are going on in our work? Are they only

informal? Are there regular meetings as well? Is there occasionally a formal

process? What, in each case, are the benefits and short-comings?

2. In our community, how do evaluating and planning take place? Are

the themes for reflection, like the ones presented, relevant to community

life?

3. Other social justice groups notice a penchant, in Jesuit projects,

for methodical thinking and critical reflection. They sometimes ask us

to help them plan or evaluate. What — out of our formation, experience

and characteristic approach — have we to offer such groups?

3.9 Administration

- pg - 65

Administration is not a topic towards which most Jesuits have a natural

inclination. However, it is worth remembering that St. Ignatius spent over

fifteen years administering the new Society of Jesus as its Superior General

and writing its Constitutions. His example is strong encouragement

to take this topic seriously. "Administration" and "management" belong

to the worlds of business or bureaucracy, while "our way of proceeding"

is a very Jesuit expression. In this chapter they come together in the

actual running of a Jesuit social centre or project.

This daily concrete running may, depending on the kind and size

of the work and on the local culture, be called action, administration,

conduct, direction, management, operations, practice or programme.

Insofar

as ours is similar to other comparable grass-roots work, NGOs, research

and action centres, these are important to refer to in thinking about our

administration.

Much of what is involved in the actual running of a Jesuit project usually

remains in the background, but that does not make it indifferent to our

mission. Here the characteristic consists in paying attention to apparently

pedestrian ones, so that "how we manage" really supports, enhances and

testifies to "what we are trying to do."

Just as earlier chapters showed how to read the situation rather

than giving a picture, so this chapter does not describe any particular

Jesuit project, much less define a correct or ideal type. Instead, it mentions

points to consider under a number of headings — place, human resources,

finances, material means. Each group needs to find what issues it ought

to attend to and apply with intelligence and creativity.

Day to day

The place we work in (a room, a building, a complex) and live

in (a house, an apartment, a residence) should be physically accessible

and culturally welcoming in a special way to the poor — the people for

and with whom we work. It should also have facilities apt for living, hospitality,

working, meeting, thinking, writing. It should be reasonably clean. What

receives prominence in the decoration — pictures, posters, images, symbols

— makes an impression deeper than many words. Does the decor say what we

want to get across?

With respect for both the donors and the beneficiaries, we use material

means and resources well: paper, books, vehicles, computers, audio-visual

equipment. We avoid a throw-away mentality and are careful not to damage

or waste. Buildings and equipment may seem "just a means" which does not

deserve attention, but something considered normal in one culture (to discard

paper, to borrow a car) may have quite a different significance in another.

The resources called "ours" have been entrusted to us to be used for

the social apostolate, for the poor, for justice. Whether or not we share

material resources with sister groups that are less well-endowed is sometimes

at issue.

"Human resources" mean the material conditions in support of

our working together: just wages, social security and other minimums of

labour justice for both professional and support staff (an important and

sometimes complicated distinction which small projects usually need not

make). They also include basic working conditions for interns and volunteers,

and the Jesuits who sometimes fit into these categories and sometimes do

not.

Pg - 66 - Promoting the work

Also related to working together are the resources of leadership which

should serve the whole project. As much as possible things should be run

with transparency and everyone on staff should be kept well informed. However,

not all staff members are equally responsible for the issues of administration,

and openness may be difficult if some on staff cannot keep confidence.

Finally, "human resources" in quite another sense are the staffs competence,

formal knowledge and learned skills, put to work together.

Þ Teamwork

(3.6)

In some countries, people involved in social justice projects and research

centres are adapting techniques of business administration for use in their

own administration. Jesuit organisations, especially larger ones, may benefit

greatly from submitting themselves to an appropriate discipline in terms

of personnel, resources, finances and fund-raising, without assimilating

a for-profit mentality.

Financial questions

Exercising responsibility for our financial resources may begin

with taking care to use money well. At a minimum this means using it honestly,

not being arbitrary, accounting for income and expenses with transparency,

and using accounting methods appropriate to the size and type of project.

Once again, while all staff members are not equally responsible for financial

issues, an appropriate level of information is important.

|

Because of the poverty situation of the Continent, many excellent

and well developed Jesuit Social Apostolate works must seek outside funds

from church organisations, foundations and private individuals to support

their capital expenditures and ordinary running costs. Over the years,

this can engender a dependency that dictates past orientations, present

operations and future prospects. Because of recent economic and political

developments outside Africa (e.g., recessions, opening up of Eastern Europe),

the source of funds is significantly declining. This has direct results

on the viability of many of our apostolates. (Africa)

|

In some case the Society of Jesus sponsors

the

social project, provides the facilities, assigns Jesuits to work in it,

provides financial resources, and consequently accepts an important moral

responsibility. other sources of funding carry responsibilities

too. Funds provided by the Church, by benefactors and sometimes by beneficiaries

are a form of cooperation or partnership. It is important to keep the sponsor

and supporters well informed.

Funding from corporations, foundations and the state may provide

an essential piece of the budget, with the risk however of making us dependent,

affecting our real priorities, and limiting our freedom to act or to criticise.

Many projects are trying to diversify their sources of major funding, but

this takes effort and may result in loss of income. |

Investments made in our own name or by the Society for us deserve

scrutiny according to principles of ethical or responsible investment.

Religious congregations and NGOs have developed such principles that are

applicable to Jesuit projects. The purpose of investment is to earn revenue

to support the work, but should we invest in corporations whose conduct

we criticise? Should we invest overseas to earn a higher yield at lower

risk, or invest in the national economy with less earnings for the social

apostolate and sometimes real danger of losing the capital?

Administration - pg - 67 -

Preparing a budget may be the occasion for reflecting on our

real priorities in what we choose to work on and spend on. A temptation

is the "economy of scale," which favours activities of greater proportion

and scope for the sake of greater efficiency or productivity and to reach

more people. Is this logic always valid for us?

Þ Planning

and Evaluation (3.8)

Despite good intentions, abuses may be committed, and there are no fail-safe

recipes or perfect solutions. The point is to be watchful, pay attention,

exercise care for persons on the basis of justice and stewardship in the

use of resources. This responsibility we accept is a question not only

of integrity as seen from within but also of the public image we project.

The public persona

The public persona of a Jesuit project, more than just image,

is essential in having an effect in society and culture:

· to communicate our concerns

· to relate with other groups

· to resist injustice, promote change,

involve others

· to influence public and political

opinion

· to protect the vulnerable (occasionally

ourselves) from attack

· to raise money or win other needed

forms of support.

| |

|

| In any encounter which people have

with our project or centre (personally, in groups or in the media), what

do they see, experience, expect and conclude? The ways in which we manage

our physical, human and financial resources translate into cultural, ethical

and spiritual impressions. Do people find us and our project competent,

cooperative, generous and reliable? How the media treat our work, the positions

we take and the causes we promote, are also our responsibility. On us depends

how we treat journalists, which groups we associate with, and what kind

of image or persona we project. Learning how to give a good interview is

a practical way to improve our media presence. |

The agencies for economic assistance have turned their eyes

and hearts to other continents. They complain moreover about the lack of

successful experiences in the struggle against poverty which endure and

serve as a repeatable model.

(Latin America)

|

A Jesuit social project fulfilling its mission projects a certain coherence

between social action and spiritual discourse. Others will testify to its

credibility, to the witness it offers, to the hope it shares, to the Good

News it conveys.

Tensions

The project/organisation/institution is a multiplier of individual efforts,

a presence or even weight in society and culture. Such a resource, providing

prestige, influence and a comfortable livelihood, can become absorbing

in itself. A well-established work does not easily shed a critical light

on itself, and criticism from without is often unwelcome.

Þ

Planning and Evaluation (3.8)

Pg - 68 - Promoting the work

Some Jesuit groups fear that concern for administration might dull the

prophetic edge of their work. This fear may be due to an unexpressed preference

for "anarchy/spontaneity" rather than running things as a team. Other groups

may Fmk the concerns raised here obsessive, introspective or self-centred

because they do not see their relevance to urgent issues and demands. Still

others, enmeshed in internal difficulties, may find the points "too little

too late" to help them out of a morass, whereas new or small projects may

see in them early signs of their future institutionalisation.

Many a Jesuit works full-time on administering a project or centre,

spending practically all his energy on management, fund-raising, public-relations,

hiring, planning. His leadership makes possible the social justice service

which staff offer. Externally, a Jesuit director is often credible in the

public realm and among supporters. Administration is a real service in

providing the conditions under which the work can be done effectively and

harmoniously, and the fact that the Society provides or helps assure the

leadership and resources is appreciated.

| The leadership of a Jesuit gives many a project

its Jesuit identity — and yet sometimes, sadly, one in the transition to

the second generation does the work really become integrated into the mission

of the Province. Those in positions leadership in the social apostolate

are invited to lead with awareness and discernment of the real tensions

underlying the choices to be made. Without interior freedom we can easily

be trapped by the apparent good of careerism or an addiction to the task

at the expense of persons. If we do not pay attention to this dynamic within

the groups and institutions in which we ourselves are directly involved,

we can end up struggling for justice and human rights while violating them

even as we strive. |

The true paradox of our apostolate is found here, of between work

for justice which is socially and culturally effective, and work for Justice

which is evangelically expressive of the Good News.

(Father General at

Naples)

|

In many concrete administrative decisions, "efficiency or professionalism"

and "social results" come into tension with "poverty or simplicity" and

"evangelical, counter-cultural witness." The debate often moves between

"principle or purity" and "organisational pragmatism or expediency." The

point here is that choices made unconsciously are better made with awareness

of the tensions involved and after discussion by the staff.

Þ

On-going Tensions (4.2)

Administration and justice

"Don't sweat the small stuff" and "Be faithful in little things"

are two apparently contradictory bits of proverbial wisdom which illustrate

the challenge of administering well a work or centre of the social apostolate.

Openness and transparency, dialogue and, sometimes, counter-cultural

courage may be necessary for a group to recognise and face the ambiguities,

limitations, temptations, even sins which mar its day-to-day functioning.

Thus, administration has a wide-ranging relevance for the justice which

every social apostolate centre or project not only talks about but also

tries to implant or promote. It is a living experiment in people learning

to work together for others, translating ideals into social and cultural

reality, testifying in deed to the Kingdom of God.

Promoting the work — Administration - 69

In conclusion we make our own the promise expressed by the Latin American

Provincials of the Society of Jesus in their November 1996 Letter on

Neo-liberalism in Latin America:

To make our undertaking credible, to show our solidarity with the

excluded of this continent, and to demonstrate our distance from consumerism,

we will not only strive for personal austerity, but also have our works

and institutions avoid every kind of ostentation and employ methods consistent

with our poverty. In their investments and consumption, they should not

support companies which violate human rights or damage the eco-systems.

In this way we want to reaffirm the radical option of faith that led us

to answer God's call to follow Jesus in poverty, so as to be more effective

and free in the quest for justice.

Questions

1. In its action and outreach, our centre or project is trying to implement

justice, reconciliation, solidarity. Are there concrete signs of these

values in the daily running of it? Are there also counter-signs, values

which ignore or deny the justice of the Gospel?

2. Could the Jesuit Province Treasurer help to develop more specific

questions for the social apostolate to raise regarding our administration,

working conditions, investments? Could someone help us reflect critically

on our public relations and presence in the media?

3. Since Jesuit community is not a "private" but an intrinsic part of

the social apostolate, are there questions of administration worth asking

about our community life?

3.10 The Jesuit

body - pg - 71-

The mission of the Society of Jesus according to the Formula of

1550, "to strive especially for the defence and propagation of the faith

and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine," was re-expressed

by GC32 in 1975 as "the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice

is an absolute requirement, since reconciliation with God demands men's

reconciliation with one another." This, added GC34 in 1995, "cannot be

achieved without attending to the cultural dimensions of social life and

the way in which a particular culture defines itself with regard to religious

transcendence" (d.2, n. 18).

This historic decision commits the Society of Jesus to the promotion

of justice at the most fundamental basis of our identity and all our activity:

our mission. "The service of faith and the promotion of justice cannot

be for us simply one ministry among others. It must be the integrating

factor of all our ministries; and not only of our ministries but also of

our inner life as individuals, as communities, and as a worldwide brotherhood"

(GC32, d.2, n.9). Therefore "the promotion of justice should be the concern

of our whole life and a dimension of all our apostolic endeavours"

(GC32, d.4, n.47). Expressing this concern and living out this dimension

have constituted an important effort of the Society's since 1975.

From the overall mission of the Society, according to the Constitutions

and

Complementary

Norms, flows the social apostolate. Its specific goal "is to build,

by means of every endeavour, a fuller expression of justice and charity

into the structures of human life in common" (NC

298). The social

apostolate consists of "social centres for research, publications and social

action" and "direct social action for and with the poor" (NC

300).

These projects and institutions and the Jesuits and colleagues expressly

dedicated to this apostolate make up the social

sector. The purpose

of the social apostolate is to work together, effectively and evangelically,

for the poor and for the Church.

Each Province maintains structures to sustain the social apostolate,

and the social sector relates in particular ways with the rest of the Province

and, reaching out, with the rest of the Society. At first sight these might

seem like issues for Jesuits alone, but they affect everyone sharing our

work, spirituality and mission.

The Social dimension

All Jesuit ministries respond to important human, spiritual and religious

needs. All want to reach and serve the whole person. This cannot be done,

according to GC32, 33 and 34, without also always confronting sin and promoting

justice in society. The commitment is strong, the idea is clear, but to

discover what the commitment means here and now and put it into

practice has not been easy. Nor have we Jesuits found it easy to help one

another in this regard. Despite the historical difficulties, however, today

there are many Jesuits and colleagues, in every sector, who show great

social concern in practice.

All Jesuit ministries are meant to integrate the promotion of justice

into their mission at one or more levels: through direct service to the

poor, by developing awareness of social responsibility, or in advocacy

for a more just social order (GC34, d.3, n. 19). There are outreach programmes

located in Jesuit universities or secondary schools in middle-class communities,

as well as educational and pastoral institutions serving people on society's

margins: Fe y Alegría elementary

Pg - 72 - Forming the apostolate

schools, inner-city (Nativity-type) middle schools with intensive programs

of education for the urban poor, urban core parishes largely engaged in

social ministries.

But unhappy memories and resistances still do damage today, and misunderstandings

continue to occur. Since Decree 4 all Jesuits have had a serious responsibility

for the promotion of justice. Therefore, some Province members fear that

they may legitimately be criticised for their work or lifestyle, denounced

or told what to do by those in the social apostolate.

The fact that there are some social projects and works and "inserted"

communities in a Province is no reason for others to "leave the promotion

of justice to the specialists." More subtly, perhaps, the fact that someone

works full-time in social research does not exempt him from the justice

dimension either, including living simply or among the poor and having

direct pastoral contact. Or the fact that a Jesuit works full-time on a

particular social project — for example, with the homeless or illiterate

day-labourers — does not exempt him from reflecting on wider social issues

of consumerism or the public stance of the Province on human rights.

Rather than trying to sort out the long-running misunderstandings, the

social apostolate proposes a kind of mutual embargo on both criticisms

and fears until such time as, understanding each another better, we can

help one another live the commitments which the Society has assumed.

The social sector

The activities of the social apostolate — "social centres for research,

publications and social action" and "direct social action for and with

the poor" — have different names in different parts of the world: social

action, social ministries or social-pastoral ministries, social justice,

social work or services, development, worker mission, work with the excluded

or marginalised, Quart monde or Fourth World.

Without wanting to replace any of the local names, we use the expression

"social apostolate" to refer generically to this great variety of activities

or

involvements in society and culture. The similar expression "social sector"

refers to the Jesuits and colleagues, projects and works from the

organisation

point

of view and distinguishes them from other apostolic sectors.

While this makes logical sense, it is not always easy to imagine or

visualise the social sector. Nearly all other apostolic sectors are typified

by a definite, often traditional institutional form. Thus, education: schools,

universities; spirituality: retreat houses; communications: publishing

and electronic media; pastoral: parishes or missions; formation: novitiate,

scholasticate.

If you ask a Jesuit, "What do you do?" and he answers "I'm in secondary

education," a significant image immediately comes up. If he adds the name

of the city, the subject he teaches or the administrative pest that he

holds, you quickly form a pretty complete idea of his ministry. By contrast,

the social sector has neither traditional institutional forms nor typical

means or instruments of its own. It is marked by nearly endless variety

and rapid change. So if to the friendly question, "What do you do?", the

Jesuit answers, "I'm in the social apostolate," no image comes up unless

he quickly spells out what he does, where, since when, among which people,

in what kind of setup, with which colleagues, to what purpose.

The Jesuit Body - 73 -

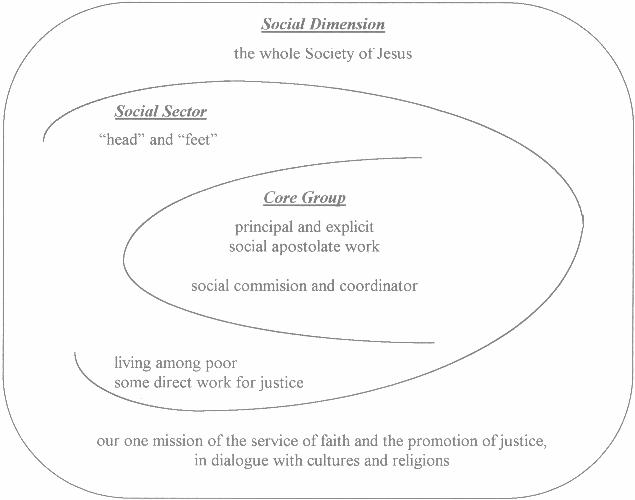

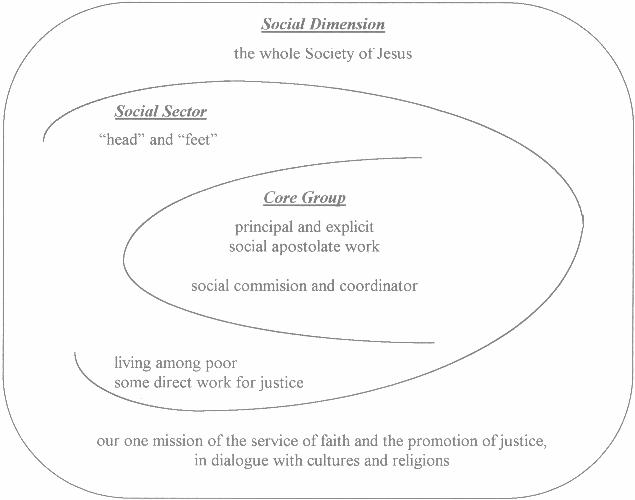

Therefore, without making unnecessarily sharp distinctions or demarcations,

it seems helpful to think of the social apostolate sector in terms

of concentric circles.

In the inner circle are the Jesuits and colleagues who work expressly

in the social or socio-cultural field, and the projects, works or institutions

explicitly dedicated to the promotion of justice, along with schools, parishes

or communities inserted in very poor areas and Jesuits working in social

institutions or projects not sponsored by the Society. Together with the

Social Commission and its co-ordinator, this is the core group.

In a wider circle are the Jesuits and colleagues who, while committed

to activities in another sector, dedicate some time to direct work for

justice, live among the poor, and have strong bonds with the core group.

This circle, along with the first, form the whole social sector. The

largest circle is the essential social dimension: the other Jesuits

and their colleagues working in other sectors, in formation or in retirement,

for whom the promotion of justice is an always present dimension of their

mission.

If, with all their heterogeneity, the individuals and works of the social

area remain scattered and unconnected, they remain difficult for other

Jesuits to comprehend and consider part of the corporate commitment or

mission of the Province. "That's not a work of the Province," it is too

often said, "but Fr. So-and-so's project.... It's within the territory

of the Province but isn't part of our mission."

Pg - 74 - Forming the apostolate

| The social sector can be for Jesuits an area